CANTO

CANTO

It is a simple, if almost incomprehensible equation: the world is as terrible as it is beautiful, but when you look more closely, it is as beautiful as it is terrible. We must maintain constant vigilance, to protect the world from ourselves, and to embrace the world as it exists.

- Richard Misrach

CANTO is a series of new works by artist Stephanie Burke. Burke works within the landscape of the American West, a landscape fraught with a complex history of human exploitation, alteration, and conservation. These issues, explored and re-explored over the vast history of the photographic image, remain fertile ground for exploration, especially in the post-millennial, post-crash, ecologically and economically conscious United States.

Christianity and the vernacular both played important parts in the forming of the American West, geographically and psychologically. Dante’s Divine Comedy, written in the plebian language of Italian rather than the more traditional Latin, defines the temporal landscape of the hereafter in stark and yet mythologically rich visual terms. Pilfering Dante’s visuals and adopted his mantel of personalizing the landscape and its inhabitants, Burke inscribes the history of her Western Hell, her Western Purgatory, and her Western Heaven onto the ever-degrading skeleton of the Divina Commedia.

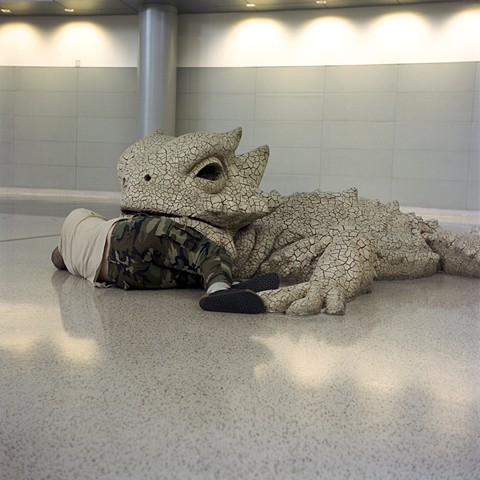

Herein desert itself defines the Inferno. Its character is that of desolation, of dark humor, loneliness, and mortality. It is one of the harshest environments on the planet, and yet exists as the generative point for many of the greatest contemporary religions. The desert is a place of hidden killers and hidden saviors, the desert is a test.

Purgatory explores the houses of power scattered through the space and resource-rich Western landscape. These domiciles of power, a logger baron’s mansion, a plutonium production reactor, a gold mogul’s summer home, now exist as tourist traps, as places for the public to gawk at the fallen splendor of these great houses. Built to keep the people out, they now welcome them with open, if brooding, arms, relying upon prole cash to stay alive.

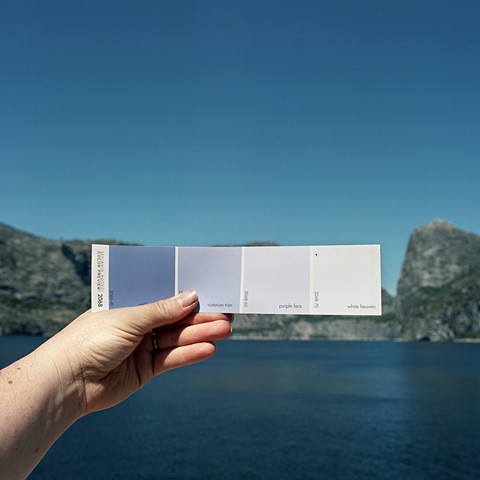

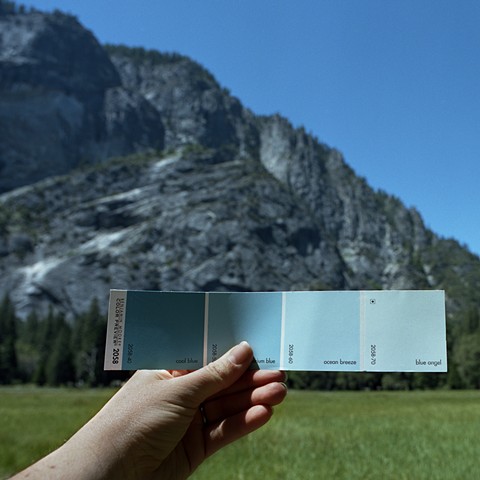

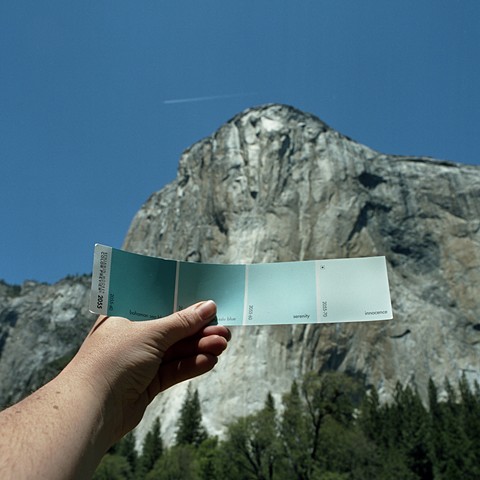

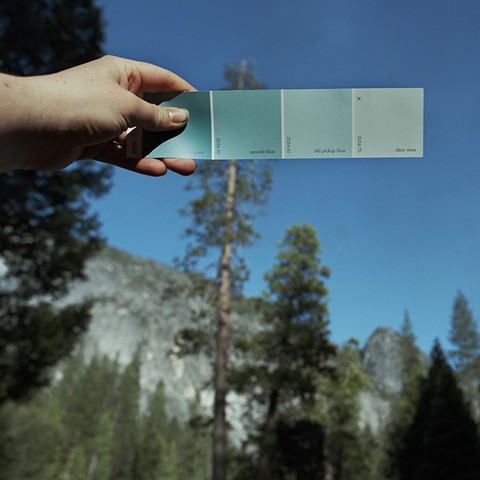

Heaven is a confusion and a mystery. The secular beauty of the world is a heaven in and of itself. Yet many attempt to grasp the great beyond, a transcendental paradise unknowable and yet constantly described, referred to, and used to control. This paradise, so often pursued through profane and garbled channels, fails to resolve the heavenly paradise while obscuring the one before the very hand and eye.